Quick Links

- Overview

- Foundational Elements

- Success Measurement Criteria

As part of COP 26, 22 countries including the United States (U.S.), United Kingdom, Chile, and Australia, signed the Clydebank Declaration, with the goal of supporting the establishment of at least six green corridors by the middle of this decade. In addition, the U.S. Department of State announced its aim to help set up green shipping corridors and provided high-level guidance on what can be expected as the building blocks for green shipping corridors.

Over the course of the next decade and beyond, green shipping corridors are expected to act as a catalyst for the global energy transition by providing frameworks for regional and international stakeholders to collaborate on maritime decarbonization goals while aligning with broader regional, national, and international decarbonization initiatives. As with all elements of the global energy transition, the number of stakeholders and the available resources, can prove challenging. Therefore, route selection must be a data-driven decision, with the goal of large-scale decarbonization and techno-economically feasible implementation.

At ABS, we are bringing together industry stakeholders to collaborate and form the foundation needed to establish a green shipping corridor. We begin by performing data analysis to inform decisions regarding selecting, establishing, and utilizing green shipping corridors. We then bring together key industry stakeholders capable of providing the necessary resources to support the designated pathway.

As with any global initiative, cooperation and collaboration are at the bedrock of any green shipping corridor and with its rich history of bringing together stakeholders from across the supply chain to achieve a common goal, ABS is poised to make this concept a reality. Some of the current green shipping corridor projects that ABS is involved in include:

- As a member of the Blue Sky Maritime Coalition (BSMC), a not-for-profit organization, ABS is leading on behalf of BSMC on developing a green shipping corridor for the Gulf of Mexico and Lower Mississippi River region.

What is meant by “Green”?

“Green” indicates that the foundational focus of the corridor is emissions reduction. According to the Clydebank Declaration, the focus is on zero-emissions maritime routes between two or more ports. The U.S. Department of State initiative considers both low- and zero-carbon maritime routes within the ambit of the definition of a green corridor.

Keeping emissions as the north star, different proposed corridors may focus on different elements of decarbonization. Certain green corridors may be fuel and technology agnostic (i.e., they take the most liberal interpretation of a green corridor). In some other cases, green corridors may be driven by the existing presence or potential development of fuel and bunkering infrastructure. Finally, there would be cases where certain green corridors may choose to clearly indicate that their corridor needs to have a technology demonstration aspect and may specify fuels that they will rely on to achieve emissions reduction.

What determines a “Corridor”?

In the context of green corridors, this specifically indicates the geographical connection between two locations (could be specific maritime routes or it could be multiple ports between two regions) and the enabling environment that helps reduce emissions.

A corridor should be defined by a bottom-up approach, created based on a detailed pre-feasibility and feasibility assessment that clearly answers the following:

- What is the business case?

- What are the alternative fuels available and infrastructure present and ease of development of new infrastructure?

- What are the policies and governmental support that help enable the development of a green corridor?

A corridor could be described as the equivalent of a “grouping” that expects all members within the physical reality to agree and operate within some commonly accepted standards that help reduce emissions.

Port-Centric versus Tech-Centric Corridors

Port-centric corridors are those that keep ports at the center of decarbonization efforts. Typically, most corridors announced are between two ports, but there are more being developed which focus on a business case that is at the center of the corridor development.

A tech-centric green corridor is like a port-centric corridor but with the focus shifted more towards technology demonstration. A green corridor may prescribe in its objectives document that certain fuels or technologies need to be considered (for technical and non-technical reasons) and provide a scope for future scaling.

There could be green corridors that are technology agnostic and want to encourage emissions reduction with currently available technologies (e.g., port decarbonization by electrification followed by liquefied natural gas [LNG] fueled vessels). All these technologies are currently available and do not require any demonstration aspect.

Connect with our team today to discover how we can assist you in establishing a green shipping corridor.

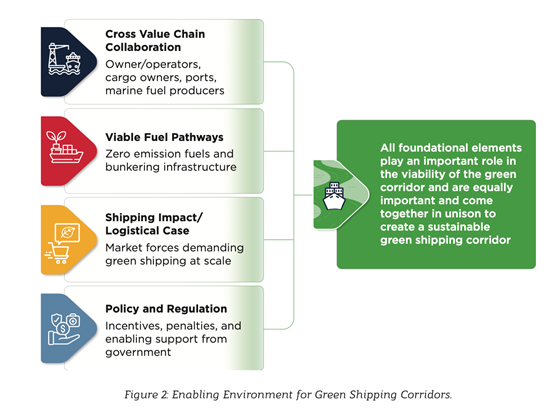

A robust green corridor should have well-defined foundational elements. The successful development of a green corridor and its continued sustenance require a set of elements to be clearly and methodically addressed. These elements will ensure the successful launch of any green corridor and mitigate any associated risk. For any green corridor to succeed, the following elements are critical and need to be clearly laid out during the pre-feasibility and feasibility assessment. There are numerous ways to define the foundational elements and the details could vary based on the specifics of the green corridor, but the broad emphasis should be on the four points listed below.

Conditions that Enable the Formation of Green Corridors

The initial selection process for green corridors is crucial. For a route to be selected as a candidate for a green corridor, it needs to have the potential for large-scale decarbonization, thereby creating the necessary impact to help the shipping sector achieve its decarbonization goals. This also needs to be feasible from an implementation viewpoint.

The selection of a green corridor is a very complex process and needs to be based on “Real-world” data that have undergone rigorous ground truthing. Each green corridor needs to undergo a detailed feasibility study that answers the following questions:

- What is the vision and objective of the green corridor? A well-defined end goal is a primary requirement, i.e., what are the corridor’s key performance indicators (KPIs), which help understand metrics of interest to be tracked.

- What is the timeline for the formation of the green corridor?

- Is a regulatory framework in place at a Country/Province/Port/City level to support a green corridor? If not, what advocacy needs to be done to create an enabling environment?

- What is the Business Case for these green corridors? What is the timeline for return on investment (ROIs)

- What are the funding sources? How much governmental support is available? Green corridors are massive undertakings, and governmental support is paramount, particularly in the port and bunkering infrastructure-green corridor interface.

- Who are the members of the consortia? Ports, vessel owners/charterers, shipyards, alternate fuel producers, class societies, OEMs, regulatory and governmental bodies.

- What are the low/zero-emission fuel options and the potential for scalability for the green corridor?

- What are the trade routes, vessel segments, and cargo types that operate between ports which are part of the green corridor?

When the above listed questions are answered rigorously, the contours of a “viable” green corridor will reveal itself which will include the following:

- Location

- Screening Business Case

- Consortium

- Funding Source

What are the critical success factors?

- Credible Fuel Pathways - Successful initiatives will be built on credible fuel pathways, the potential for value chain initiatives, and the feasibility of policy action.

- Business Case - Green Corridors are emission reduction projects but their critical path is based on a sound business model.

- Scale - Corridors should be large enough to embrace all relevant value-chain actors, such as fuel producers, cargo owners, and regulatory authorities. They can provide offtake certainty to fuel producers and enable vessel operators, shipyards, and engine manufacturers to prioritize investment in zero-emission shipping by de-risking the operational environment.

- Funding - The green corridor should have stable funding sources, including governmental support, to help during the take-off phase.

- Certifiable Data - Regular and transparent information with verified, trusted data will also be critical.

In short, success factors are corridor-level consensus on fuel pathways, policy support to help close the cost gap for higher-cost zero-emission fuels, and value-chain initiatives to pool demand as well as transparent, reliable data and reporting.

Other important factors to be evaluated

Examples of the kind of decisions key stakeholders will be making include:

- How shippers choose to direct cargos through multiple Corridor options

- How shippers report carbon footprint of products moved through a Corridor

- How customers select passenger vessel transportation options based on Corridor reporting

- How local/regional clean energy coalitions incorporate Corridors into their broader strategies (e.g., Green Shipping Corridors as part of Hydrogen Hub strategies)

- How agencies direct grant program funding to support development/expansion of Corridors

- How communities, especially residents in communities with environmental justice concerns, engage with Corridor developers to address priorities and goals of near-port communities

A very important aspect in the development and continuous successful operation of a green corridor is the need for a palette of metrics in place to quantify the decarbonization effect of the initiative. The emissions scope, boundary and metrics will vary based on the jurisdiction of each of these corridors and the level of ambition they aim to achieve.

Life-cycle Emissions Estimation

Fundamentally, a green corridor’s success is a function of its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction potential and for that to be a controlling metric, the calculations need to be robust and should follow commonly accepted standards such as ISO 14064-1, GHG protocol requirements and other maritime industry specific methodologies. To further improve confidence in the estimation, they may need to be assured or certified by independent third parties.

To improve the robustness of maritime emissions estimations, life-cycle analysis (LCA), which is the estimation from well-to-tank (WTT) and tank-to-wake (TTW) of the fuel related emissions, is the commonly accepted norm for estimating the impact of each value chain stakeholder of the corridor. Each of the value chain stakeholders should clearly demarcate their boundary and consistently calculate their baseline emissions. The baseline emissions profile should be an indication of the current operations prior to conversion to a green corridor. For example, what is the emissions estimate currently without the aspects of the green corridor considered, including both a current day snapshot and a future forecast.

Shipyard Emissions

Shipbuilding emissions may not apply to all green corridors but will be a very useful metric to consider when converting existing traditional routes to green ones, since many of these projects will require newbuilds and retrofitting of existing vessels. Shipbuilding emissions can be divided into hull (material and protection) and machinery (main and auxiliary) impacts and play a major role in understanding the emissions over the entire life cycle of a green corridor.

Baseline Emissions Inventory for Port and Vessel Operations

Port emissions inventory will be a major component of the GHG footprint of any port-centric corridor since, fundamentally, the decarbonization will revolve around vessels and port decarbonization which will include electrification of shore-side infrastructure and development of cold ironing facilities to reduce vessel emissions while waiting at the port. Port emissions are typically from mobile sources and then can be divided into the following categories:

1) Ocean-going vessels when berthed in the port

2) Harbor craft

3) Cargo handling of the equipment

4) On-road vehicles

5) Rail

Ports are such a critical stakeholder in the development of a green corridor, they can take the lead utilizing governmental incentives to decarbonize and signal intent which will help build momentum towards decarbonization of the shipping industry. Currently, U.S. EPA, Environment and Climate Change Canada and other private non- governmental research organizations provide detailed methodologies and guidance on conducting a port inventory. The challenge is that there is very little overlap on methodologies, scope and boundaries, requiring clarification before inventory development since all the ports need to have a commonly accepted baseline inventory with similar assumptions.

Independent Verification

Since the green corridor’s fundamental goal is to achieve carbon emissions reduction, it is important that the methodologies, emission factors, activity data and calculations are certified by an independent third party with a detailed audit trail. There are numerous organizations that certify carbon avoidance and emissions reductions to maintain the environmental integrity of the project.

This will also allow project stakeholders to obtain robust reduction and voluntary carbon credits which could play an important role as a revenue stream and push many of the economically unviable projects into the green.

The assessment will include calculations of baseline GHG emissions or baseline GHG removals by sinks followed by calculations of project GHG emissions and actual net GHG removal by sinks. The process also takes into consideration leakage to arrive at an actual GHG emissions reduction or net GHG removal value.

The infographic below indicates a high-level vision of an operational green shipping corridor.

- Decarbonization pathways involve accelerating operational efficiencies and deploying alternative fuels at scale. The industry is diverse, disaggregated and globally regulated.

- Green Shipping Corridors help facilitate the coordination between stakeholders down to a more manageable size while retaining scale.

Any combination of these fuels and technologies could apply based on the techno-economic feasibility of the corridor in question.